Here’s a very interesting and titillating story: around the year 410 B.C., the men of Crotona, then one of the wealthiest cities in Italy, wanted to improve their already well-known temple to Juno, wife of Jupiter. The ruins of the once-magnificent temple are still visible today by the sea near the southern tip of Italy.

According to Cicero (On Invention, 2.1), the men of Crotona decided it would be worth the immense price to hire the famous painter, Zeuxis of Heraclea, to add a grand fresco depicting the most beautiful woman of all, Helen of Troy, to one of the walls of the temple to Juno.

Helen had long been known in the Greek and Roman worlds from the time of the Iliad, and if she was not just a poetic invention, she lived at least 800 years before Zeuxis the painter. His task was therefore comparable to a painter today being assigned to paint an image of the beautiful Guinevere of the King Arthur myths. Consider for a moment: if you were a master painter, how would you go about imagining a woman reputed to be “most beautiful,” if you have almost no other details to work with?

I’ll get back to the story itself in just a minute, but I want to comment on my interest in the story. The issue raised by the story is whether and how we can understand (and depict) a Platonic transcendental form like “beauty.” It’s closely related to a criticism often leveled against existentialists, postmodernists, and others who think outside of an orthodox tradition. The charge is, “How do you even know what the good is—or what beauty is?” —that is, if the church has not pre-defined these things for you?

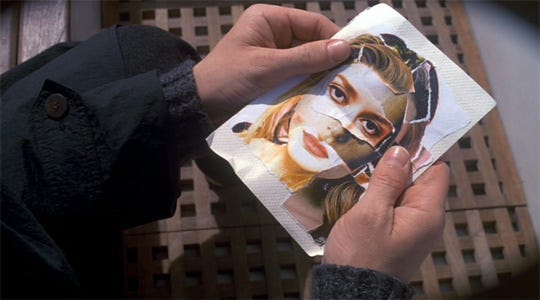

What Zeuxis did became a legend in itself: he held public call of sorts—the most beautiful virgin women of Crotona were gathered together, and he carefully selected five of them. He would use various parts of the five models, and weave them together into a single painting—a Frankenstein’s monster approach—to create the immortal image of Helen of Troy. There are a number of well-known paintings commemorating the scene of Zeuxis selecting his models:

What was he looking for, and how would he recognize it? The idea here is that the recognition of beauty (or of the good) is a kind of intuitive thing—”it is written on our hearts,” to paraphrase the Apostle Paul. Perhaps many years of experience refined his aesthetic sense, but with “Beauty” as his only guide, Zeuxis was able to construct, from an assemblage of partial perfections, a unified vision of the beautiful Helen.

I recently read a good piece about all of this on a blog I follow, but I thought I could add half of an idea. The blog linked there discusses the pastiche approach to beauty as a kind of “monstrosity,” as an unsettling symbolic violence against women—classic grad school take, in my opinion. My little contribution would be to suggest that, instead, this is how everyone relates to the Platonic ideals. We take the good humor of our little league coach, the moral seriousness of our first pastor, the steady loyalty of our dad, the irony and sarcasm of our middle school best friend, and we piece all of this together to form an image of the Good — and perhaps we try to make our own personalities match that image.

Interesting footnote here: one of the models selected by Zeuxis was the famous courtesan, Phryne, who was once brought to trial by Hypereides for blasphemy and public indecency. According to most tellings, Phryne was about to be convicted and sentenced, but she exposed her perfect breasts to the gentlemen of the jury, and she was exonerated—the men concluded that a woman so favored by Aphrodite could not be guilty.

That’s pretty funny, isn’t it? Don’t be surprised that there are also a number of well-known paintings of that scene—for me, they sort of beg the question: how should the perfect rack look in a painting? Is it like either of these representations?

To be honest, I think I’ve seen better. I know this is sort of low-hanging perky fruit, but if you’re thinking about it at all, then you’re already familiar with the kind of thought that is commonly criticized by the religious traditionalists and orthodox. They say that trying to discern “the Good” for yourself is a mistake. “That’s subjectivism,” and “you’ve been misled by the postmodernists.” Or: “you’re just projecting your preferences, rather than the Good itself.”

There are a number of nice sculpture of Phryne too, but I’ve never quite seen one that would actually make me vote not-guilty. Look at these, though:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to An Altar of Unhewn Stone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.