I spent my morning reading Maximus of Tyre, who flourished in the late 2nd century, A.D. A contemporary of Lucian, he was a Greek rhetorician, a devotee of Plato, in an age where Christianity was spreading rapidly. He belongs, like Lucian, to the so-called “Second Sophistic” period, which tried to generate a sort of Greek Renaissance by imitating the style and themes of Plato in a later age.

His “Dissertations,” also called his orations, are extant, and readable here. He is concerned primarily with the nature of God, and explores the subject of love at great length. His first dissertation, titled “What is God According to Plato,” was among the best I read this morning. He seems to be hyper-aware of the ineffable and transcendent nature of the dæmon, and so his writing about God is circumlocutory, and he returns to a questioning posture over and over again in the Dissertations.

As you might imagine, this resonates with me. One of my favorite passages appears at the end of Dissertation XIX — it’s a bit long, but check this out:

I shall believe in the prediction, if I find it is not dissonant. Deliver to me an according oracle; for I require such a divination as may enable me to live securely. Where then do you send the race of men? In what paths? To what end? Let this end be one, let it be common. But now I see many colonies of philosophy sent different ways, just as Cadmus was sent to Boeotia, Archias to Syracuse, Phalanthus to Tarentum, Neleusto Miletus, and Tlepolemus to Rhodes. It is necessary, indeed, that the earth should be distributed by places, and that different parts of it should be inhabited by different men; but good is one, indivisible, abundant, unindigent, and sufficient to every rational and dianoetic nature; just as one sun is the one good of a visible nature, one music of a nature capable of hearing, and one health of a nature invested with flesh. But with respect to other animals, one good is distributed to every herd for its preservation, and those of a similar species partake, with their like, of an equal life, and of one end, each with each, whether they fly, or walk, or creep, or live on flesh or grass; whether they are gregarious, tame, or wild; and whether they are horned, or without horns: and if you change the lives of these you act illegally towards nature. With respect, however, to the herd of men, which is observant of law, most mild, most social, most rational, there is not only reason to fear that vulgar desire, irrational appetites, and vain loves may dissolve and divulse it; but philosophy, also, the most stable of things, produces many tribes, and ten thousand legislators, and thus divulses and disperses the herd, and sends its votaries to different pursuits; Pythagoras to music, Thales to astronomy, Heraclitus to solitude, Socrates to love, Carneades to ignorance, Diogenes to labours, and Epicurus to pleasure. Do you not see the multitude of the leaders ? Do you not see the multitude of the standards? Where can any one turn himself? To which of these shall I betake myself. Which of their precepts shall I obey?

Remarkably, that’s how Dissertation XIX concludes. If you read that closely, you’ll certainly perceive an echo of my own thinking, and a precursor to our own age: Maximus swam in philosophical waters we would describe as “postmodernist.” And it was questions that kept him afloat.

I think philosophers should make a careful distinction between reasoning and dogma. There is a tendency, which has become at various points in history a “tradition,” to accept that dogma is simply crystallized reasoning. But I don’t think that’s accurate. One accepts dogma on faith, without going through the reasoning — that is the nature of dogma. Reasoning is a different, and perhaps more tedious, approach to life. It anchors itself in perception. It asks, “what do we really know for sure, and how do we know it?” Reasoning starts again each day, and when it cannot answer its own questions, it does not push beyond itself.

One of the other interesting angles offered by Maximus is his insistence on something we might call predestination. In an early dissertation, he asks how men can have free will if there is divination? Which is to say: if the liver of sacrificed animals can tell the future, how can men choose? Later, this thought generates a sequence of sharp questions (near the conclusion of Dissertation XXII). He writes,

…that I may not lead you far from things before your feet, do you think that Socrates himself became a good man from art, and not from a divine allotment? According to art, indeed, he was a statuary, receiving this allotment from his father; but, according to the election of divinity, he abandoned his art and embraced virtue.

The wisdom of Socrates, according to Maximus, was something given directly to Socrates by the divinity. And the broader implication is that wisdom cannot be taught — it is not learned the way other arts (or trades) are learned.

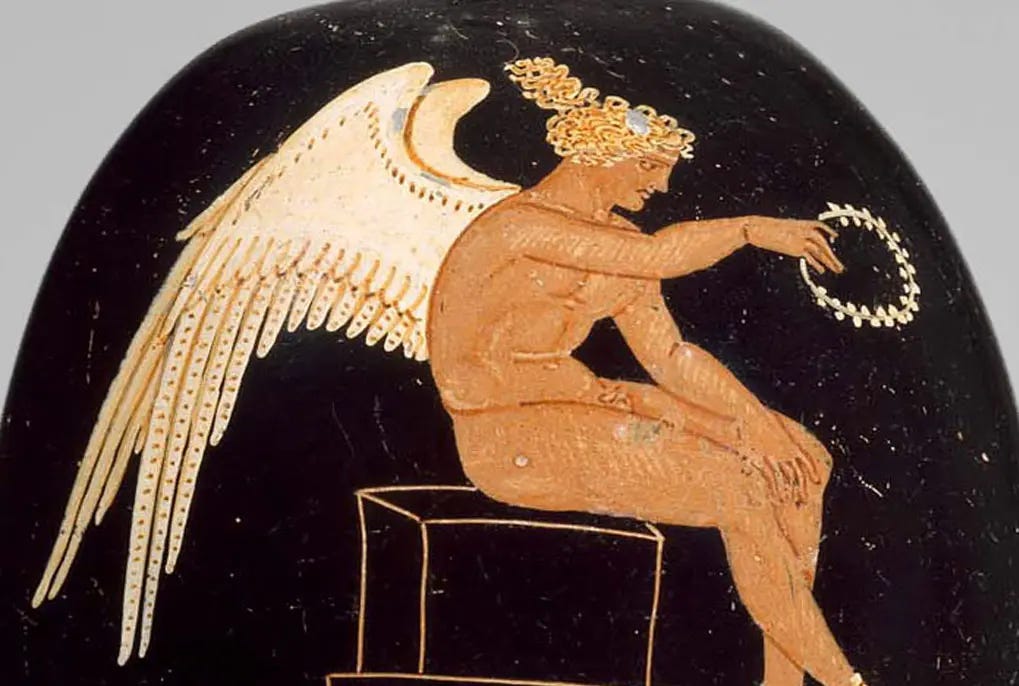

There are numerous precursors in Maximus, like the one I just described, to theological insights. On this point, if I would recommend any one of Maximus’ Dissertations, it would be XXVI, an essay titled “What the Dæmon of Socrates Was.” It’s a quick read — will take you ten minutes. In the essay, Maximus is addressing what must have been a really-existing portion of the reading public: those who believed in the divine nature of the oracles, but questioned Socrates’ knowledge of the divine (by way of his dæmon).

Ultimately, Maximus concludes on a note that puts him at odds with all dogmatists:

…as numerous as are the dispositions of men, so numerous, also, are the natures of daemons.

Still, all these daemons are uplifting of the persons they inhabit. In the final line of this essay, he argues that men of depraved souls are the only ones who are destitute of their own daemons. The takeaway, if I understand him right, is that each man has a personal daemon — something like a guardian angel. And these angels place upon different men different obligations. The theological implications almost leap from the page, and I think they are worth (re-)considering in a non-dogmatic manner.

I think I’m a Maximus maximalist! Join me.